Few people know that Chicago created one of the largest streetcar systems in the world. In 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression, the red streetcars of the Chicago Surface Lines (CSL) ran on the city’s main streets. They carried nearly 900 million passengers a year. Despite the popularity of this mode of transportation, it disappeared 30 years later. We will discuss the history of streetcars in Chicago in more detail on chicago-future.com.

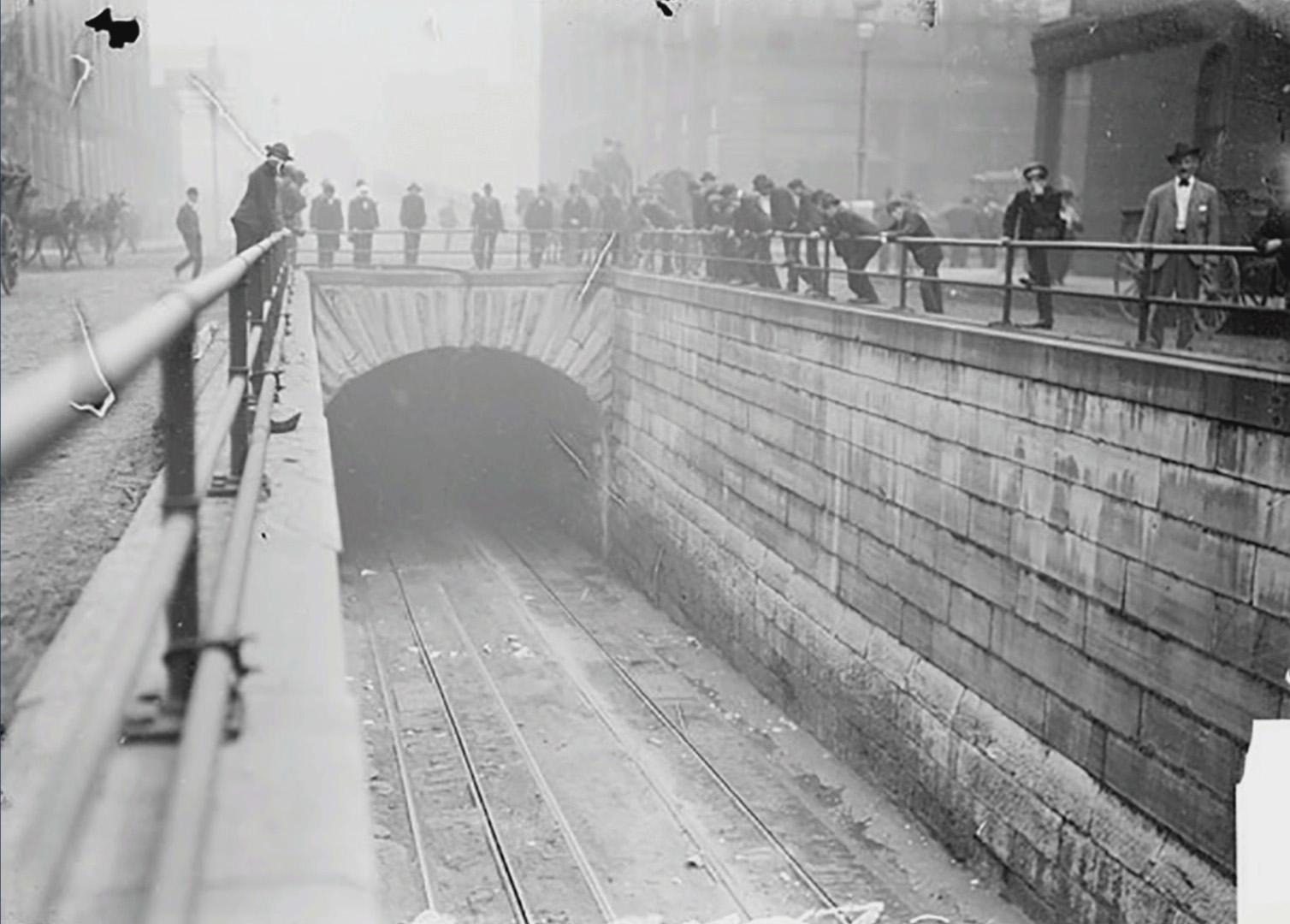

Tunnel Construction

By 1890, Chicago had grown into a huge metropolis whose residents prided themselves on their developed system of street railways. The start of urban public transit was marked by omnibuses, which led to a large network of horse-drawn railways in the city. Chicago companies adopted the cable car as an upgrade to horse-drawn transport, rather than a separate network. Horse-drawn carriages were often attached to the cable car system, which pulled them into the city center. Unable to cross the moveable bridges, three tunnels were built for the cable cars under the Chicago River.

The first opened in 1869 on Washington Street, and the second, LaSalle, opened in 1871 and was vital for the evacuation of people fleeing the fire after the wooden bridges burned down during the Great Fire. Notably, it was fabricated from steel above ground and then lowered into a trench at the river bottom. It was closed to traffic in 1939. Initially, the tunnels were intended for carriages and pedestrians. Later, the cable car companies laid tracks through them, as they could not run cables across the drawbridges. A third tunnel was built on Van Buren Street and existed until 1924. By 1890, the city’s railway network was the largest in the world. It comprised about 38 routes, and its rolling stock included over 3,200 passenger cars and 1,000 miles of track. Starting in 1892, electric traction quickly supplanted the complicated cable technology, and the last cable car in Chicago operated in 1906.

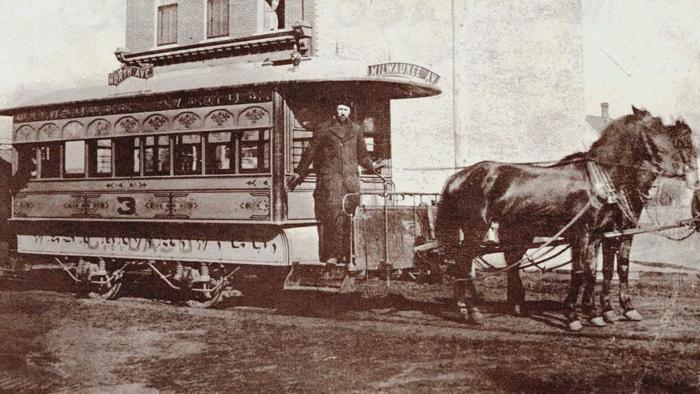

The Era of Omnibuses and Horse Cars

In 1852, omnibuses—large, horse-drawn carriages seating 30 passengers—appeared in Chicago. They transported travelers between the new train stations and hotels. The first street railway, or horse car, opened in the city in 1859. Horse cars, seating 20 passengers, were pulled by one or two horses along rails laid on the streets. They operated in Chicago until 1906.

Soon after the introduction of horse car lines, owners began searching for a mechanical traction system. In the 1880s, the approximately 6,600 horses owned by the streetcar lines and working on the routes left a lot of feces and urine on the city streets. In 1871, a large number of horses died during the Great Fire, and the surviving animals were wiped out by an epidemic in 1872.

Great Innovation: Cable Streetcars

In 1867, attempts were made in Chicago to replace horses with small steam locomotives, which were nicknamed “dummies.” However, city residents opposed them due to the smoke, noise, and sparks they produced. In 1882, the Chicago City Railway (CCRY) on the South Side adopted the cable car technology used in San Francisco. The CCRY cable line on State Street proved so popular that Chicago railways eventually built over 80 miles of lines, creating one of the largest systems in the world. Cable streetcars—as they were called because they attached to a continuously moving rope—began running on the city streets. Huge steam engines housed in central power stations pulled miles of cable through conduits dug beneath the streets. A cable car operator powered the car by attaching a grip to the continuously moving cable.

Charles Daft demonstrated an electric streetcar in 1883 at the Chicago Railway Exposition, and Frank Sprague built the first successful electric streetcar system in Richmond, Virginia, in 1888. Chicago’s cable lines transitioned and began rebuilding into electric streetcar lines after 1890, a task that was fully completed in 1906. Electric cars were much cheaper to operate than cable cars, and they could accommodate more passengers. Since 1864, streetcar companies existed on the West, North, and South Sides of Chicago, along with a number of smaller enterprises in separate districts. In the 1880s, Charles Yerkes acquired the West and North Side systems and began consolidating them. This task was completed by the end of 1900. By 1920, Chicago had 2 main systems and 3 minor ones. A total of 5 companies operated in the suburbs.

Streetcar travel left much to be desired. Traffic jams constantly plagued the roads in the Loop area, slowing down crowded streetcars. Public frustration was fueled by the corruption of magnate Charles Yerkes and the notorious “Gray Wolves” faction of the city council, which required property owners to consent to the construction of streetcar lines in front of their lots.

The Battle for Supremacy

Beginning in 1907, the city and then the state began regulating and taxing urban railways. They maintained the established 5-cent fare limit from 1859, despite inflation that led to increased costs. In the last decades of the 19th century, railways were very profitable. By 1907, they struggled to attract capital for modernization and expansion. Although automobiles gained popularity in Chicago in the 1920s, the largest street railway, the Chicago Railways Company, filed for bankruptcy. Significantly, passenger traffic was at record levels at the time. When it proved impossible to reorganize the streetcar lines as a private enterprise, the state created the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) to buy them out. In 1929, the Presidents’ Conference Committee was organized and decided that to halt the decline in ridership, streetcars needed to be as fast, convenient, and comfortable as automobiles.

Notably, two experimental designs were tested in Chicago. The winning design became known as the PCC streetcar and was used in cities across the country. Chicago ordered 600 of these cars in 1945. They were nicknamed the “Green Hornet” streetcars here for their speed and the green livery of the Chicago Surface Lines. At the same time, the Chicago Surface Lines and the “L” line were merged into the CTA. General Manager Walter McCarter ordered the gradual phase-out of streetcars in favor of buses.

The End of the Streetcar Era, A Lasting Memory

The last suburban streetcar ran on the West Town line in 1948, and the last Chicago streetcar ran on Vincennes Avenue on June 22, 1958. Notably, the high costs, active use of automobiles, excessive regulation, and the migration of the population to the suburbs led to the collapse of streetcars in Chicago. By 1907, the streetcar lines were experiencing a decline in profits due to city and state regulation, and they lacked the money to build new lines in the suburbs. The bankrupt CSL system, which included all 5 streetcar companies, was bought by the Chicago Transit Authority in 1947 for $75 million. Investors lost $110 million on the deal.

Remnants of the streetcar system still exist in modern Chicago. Many of the CTA bus routes and route numbers are the same as those from the streetcar era. As for the rails, they were removed on some streets, but most were simply covered with asphalt. PCC streetcars still operate in many places, including Kenosha, Wisconsin, San Francisco, and the Illinois Railway Museum.