At the intersection of art, architecture, and life philosophy lies one of modern America’s most iconic symbols—the Robie House in Chicago. Created in 1909 from a design by Frank Lloyd Wright, this home became not only a groundbreaking architectural statement but also a manifesto of the “Prairie Style,” which would define the look of 20th-century American suburbs. Its horizontal lines, broad eaves, integration of space and nature, functionality, and harmony—all combined to make the Robie House a true masterpiece of world architecture, earning it a place on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Read more at chicago-future.

Architectural Concept

The Robie House is a three-story residence spanning over 840 square meters (9,000+ square feet) with four bedrooms and a three-car garage. The architect divided the structure into two asymmetrical parts, which he referred to as “vessels.” The south wing contains the main living areas, while the north wing holds the auxiliary rooms. This composition provided a perfect balance between open space and privacy.

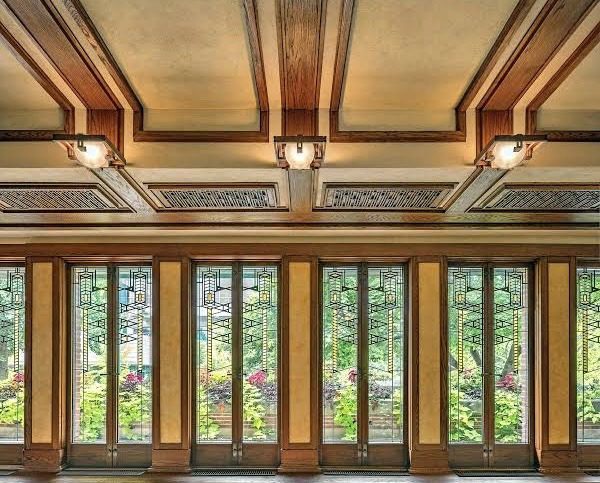

The facade is finished with Roman brick, adorned with concrete details and decorative stone. Wright deliberately emphasized the building’s horizontality—the defining feature of the Prairie Style. Large roofs, multi-level terraces, and art-glass windows create a sense of unity with the landscape. Inside, the floor plan is open: the living room, dining room, and kitchen flow into one another, a radical concept for the early 20th century. Light plays a key role: large panoramic windows with colored glass ornamentation allow soft daylight to flood the space.

Frederick Robie, a young entrepreneur and director of the Excelsior Supply Co., dreamed of a modern, technologically advanced home. His desire to combine light, space, and security resonated with Wright’s creative worldview. He wanted a house without excessive decor, with natural lighting and an open plan that would allow him to see outside while remaining unseen by passersby. This very approach became the foundation of a new architectural mindset, which Wright would later call organic architecture. Robie, his wife Lora, and their two children moved in in May 1910. The house cost $59,000—an enormous sum for the time. However, the family lived there for only one year. After financial troubles and a divorce, Robie sold the home, which subsequently changed owners several times but retained its architectural spirit.

Decades of Change

In 1926, the house was purchased by the Chicago Theological Seminary, which used it as a dormitory and classroom space. Between 1941 and 1957, the seminary attempted to demolish the structure for new construction, but public outcry saved the landmark from destruction.

In 1958, developer William Zeckendorf bought the house and donated it to the University of Chicago. This began a new chapter in its history—its transformation into a cultural and research center.

The University of Chicago undertook several major restoration phases. In the 1960s, the house hosted the Adlai Stevenson Institute of International Affairs, which held academic conferences and seminars. Since 1997, the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust and the National Trust for Historic Preservation have jointly operated Robie House as a museum of 20th-century architecture. In the 2000s, a major restoration led by Gunny Harboe Architects began, covering not just the facades but the interiors as well. The roof was replaced, terraces were reinforced, and the original furniture and color palette were restored. Thanks to grants from the Getty Foundation, the Pritzker Foundation, and U.S. government programs, the work continued until 2019, when the house reopened after a complete renewal. Today, it is not just a museum but a living laboratory of Wright’s architecture, where visitors can experience the spirit of modernism from the early 20th century.

Designing the House

In the Robie House project, Frank Lloyd Wright sought to transcend the traditional idea of a home as a collection of rooms. For him, architecture was a living organism where every element had its own function and emotional logic. He wasn’t just creating a building; he was creating a holistic living space where a person could feel part of a harmonious world. Every line in the Robie House has meaning. The horizontals that stretch along every floor symbolize calm and stability, while the vertical elements, almost imperceptible, only emphasize the scale and space. This balance fostered a sense of security and equilibrium for the resident.

Architects worldwide, from Le Corbusier to Richard Neutra, studied the Robie House as a model of organic design. Its influence can be seen even in modern homes with spatial flexibility and transparent boundaries between interior and exterior.

The Robie House demonstrates a unique combination of industrial precision and handcrafted artistry. Wright carefully selected every material to create a unified artistic ensemble. The Roman brick, with its elongated proportions, emphasizes the facade’s horizontality. Between the bricks is a thin layer of mortar, visually stretching the lines outward and making the building appear lower and more massive at the same time. The interiors are adorned with oak, adding warmth and natural texture. The original art-glass windows with geometric patterns, created from Wright’s sketches, not only serve a decorative function but also regulate light. Through them, soft sunlight transforms into a golden stream that fills the rooms with tranquility. The furniture, light fixtures, fireplace grates, even the rugs—everything was designed specifically for this home. Every object is part of the architectural system. This demonstrates Wright’s main principle: “form and function are one.”

Innovations

For its time, the Robie House was technologically advanced. The house included a central heating system, ventilation, concealed lighting, and a three-car garage—an unheard-of luxury for the early 20th century. The windows and doors had special metal frames that provided better insulation and security.

Wright also developed a unique zoning system where public, private, and service spaces did not mix. The children’s rooms, bedroom, and study were located on the upper floors, while the living room, terrace, and dining room created an open atmosphere for guests. The fireplace, which Wright considered the symbol of the domestic hearth, deserves special attention. It is located in the center of the house and simultaneously divides the space.

Over the years, the Robie House became not only an architectural but also a cultural icon. It is often called the “manifesto of the Prairie Style.” Copies of its design elements have been used in film and advertising, and numerous U.S. architectural schools have included it in their curricula. In 2019, after a multi-year restoration, the Robie House reopened its doors to visitors as a museum and center for the study of Wright’s architecture. Tours allow visitors to see not only the restored interiors but also archival documents, sketches, and photographs from the construction process.

The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and is protected as a UNESCO World Heritage site. It has become part of the Frank Lloyd Wright Trail, an architectural path that connects over 40 of the master’s structures across the country.

The house became an architectural metaphor for the United States—a country where space, light, and humanity create a timeless harmony. It reflects the idea that architecture can be simultaneously practical and poetic, modern and eternal. The Robie House continues to inspire architects, designers, and artists worldwide. Its influence can be felt in minimalist interiors, eco-design, and the open-space concept. This is not just a house, but a living philosophy embodied in brick, wood, and glass.