This is not just a high-rise office building from the late 19th century. It became an architectural manifesto of its time, embodying the transition from stone structures to steel frames and, simultaneously, a symbol of American pragmatism. From a bold experiment to a National Historic Landmark, this building’s journey reflects the very spirit of a city that has repeatedly risen from the ashes. Read more at chicago-future.

An Architectural Experiment

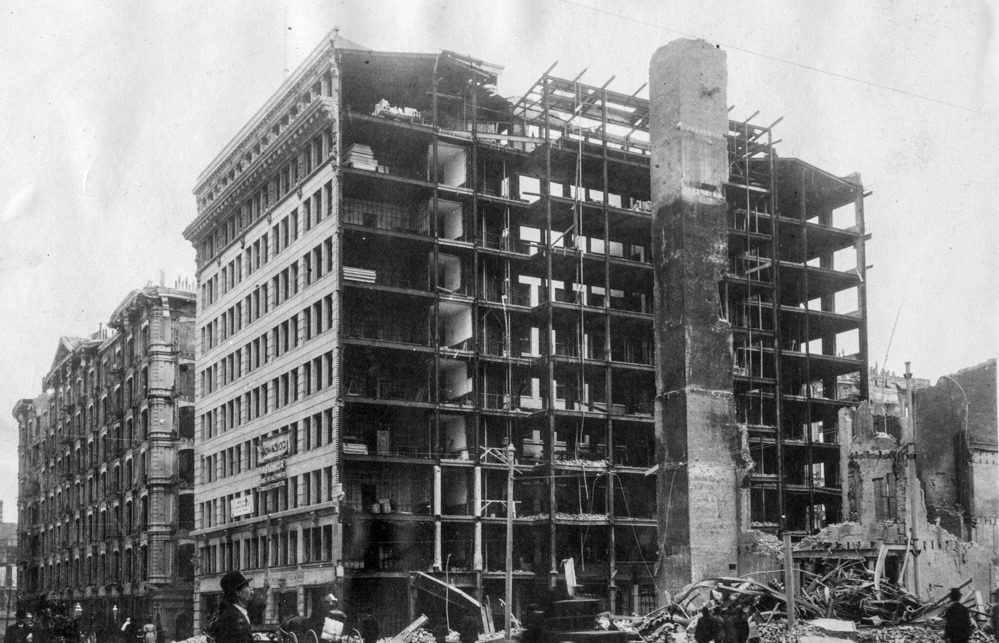

In the 1880s, brothers Peter and Shepherd Brooks, wealthy investors from Boston, decided to build a new type of office building in Chicago. After the 1871 fire, the city was experiencing a massive construction boom, and the first skyscrapers were emerging on the horizon. Project manager Owen Aldis, one of the pioneers of modern commercial development, brought in architects Daniel Burnham and John W. Root—the future creators of Chicago’s architectural identity. Their task was singular: to create a structure that was maximally functional, durable, and yet economical. Root rejected all decorative ornamentation, focusing instead on mass and simplicity. This led to the design of a monolithic, unadorned, 16-story “giant”—the tallest building in the world at the time with load-bearing brick walls.

The Monadnock was originally conceived as four separate office structures. Each section stood on its own parcel of land, with its own entrance, elevators, heating system, and even its own name. From north to south, they were named Monadnock, Kearsarge, Katahdin, and Wachusett—all named after U.S. Navy ships and mountains in New England, where the developers hailed from. This feature allowed the building to function flexibly, like several independent entities, which suited the entrepreneurial spirit of late 19th-century Chicago.

A Technical Breakthrough

The Monadnock was an architectural challenge. Its 6-foot-thick walls at the base supported incredible weight, while an internal frame of cast iron and steel prevented wind-related structural failure. It was the first step toward the “steel” future of skyscrapers. Root also implemented an innovative wind bracing system using metal portal connections, which ensured the building’s stability.

The interior was impressive in its elegant simplicity: marble staircases, mosaic floors, and light that filtered into the central corridors through frosted glass. Even aluminum, an extremely expensive material at the time, was used for the first time in its decorative staircases. Despite doubts from critics and skepticism from investors, the Monadnock quickly proved its viability. Within months of its opening in 1891, all its offices were leased.

A New Architectural Language

The northern half of the Monadnock was the final and most daring project of architect John Wellborn Root. He died at only 41, while construction was still underway. At that time, Root and his partner Daniel Burnham headed the largest architectural firm in Chicago and were designing the World’s Columbian Exposition, set to open the following year. Root’s death forced Burnham to focus on the exposition, and when the northern half of the Monadnock filled quickly with tenants, the owners decided to build the southern addition. For this, they hired a different firm: Holabird & Roche. Their version of the Monadnock retained the overall form but added more light and ornamentation: a neoclassical copper cornice, symmetrical red granite entrances, and more refined windows. The architect believed that beauty should come from form, not ornament.

Unlike the earlier section, the southern wing was built using a steel frame. This allowed for thinner walls, faster construction, and more leasable space. This technology would soon become the standard for all skyscrapers worldwide. The exterior walls were no longer load-bearing, becoming “curtain walls”—lightweight facades that merely protect the building from the elements. In 1893, the Monadnock became the largest office building in the world, with over 1,200 rooms and 6,000 workers—a true vertical city.

In the 1930s, the Monadnock fell into decline as new, modern office towers overshadowed older buildings. However, in 1938, manager Graham Aldis initiated a large-scale renovation—one of the first in the U.S. Working with architects Skidmore & Owings, he modernized the lobbies, offices, first-floor shops, and updated the elevators and engineering systems. This was a breakthrough in the concept of preserving historic buildings through modernization rather than demolition. After World War II, the building changed owners several more times and underwent partial reconstructions until, by the 1970s, it was on the verge of ruin. Some staircases were closed, the mosaic was destroyed, and the facade was covered in paint.

The Great Revival

In 1979, the Monadnock was purchased by architect and developer William Donnell, who decided to restore its original grandeur. Lacking sufficient funding, he tackled the project in phases, restoring it floor by floor. With the help of preservationist John Vinci, Donnell undertook one of the most meticulous restorations in the history of American skyscrapers.

From original drawings and old photographs, every detail was recreated—from the varnish tint to the glass partitions. Artisans crafted replicas of light fixtures with carbon-filament bulbs, and marble was ordered from the same Italian quarry used a century before. The National Trust for Historic Preservation later named the project one of the finest restorations of the 20th century.

The Monadnock is striking in its austere beauty. The northern section is massive, unadorned, with gentle curves in the walls reminiscent of an Egyptian column’s shaft. The southern part is lighter, with ornamentation that hints at a new era of architectural rationalism. Together, they form a harmonious composition that blends two philosophies—old and new. The building’s narrow form ensures natural light for all offices. Corridors are adorned with marble and glass, allowing daylight to pass through and creating an effect of openness. Here, architects Burnham & Root laid the foundations of functionalism—a design subservient to utility, not decoration.

Following the restoration’s completion in the 1990s, the Monadnock became a model for historic preservation programs across the U.S. It is part of the Printing House Row District, alongside the Fisher Building, Old Colony, and Manhattan Building—a quartet considered the heart of the “Chicago School” of architecture. The building houses over 300 tenants, from small law firms to creative studios. The first floor is occupied by small shops that retain a 19th-century atmosphere—a barbershop, a stationery store, a flower shop. The Monadnock has not only survived in the new millennium but has become a symbol of how history can coexist with modernity.

The Monadnock Building is perceived not just as an office center, but as an architectural manifesto. It is living proof of construction’s evolution, where two philosophies—traditional and innovative—meet under one roof. The northern part symbolizes the end of the era of massive brick walls, while the southern part marks the beginning of the age of steel skyscrapers. The Monadnock was not just a building; it was an experiment that defined the future of architecture in Chicago and the world.